Eco: From eft to newt, the complex life of a CT amphibian

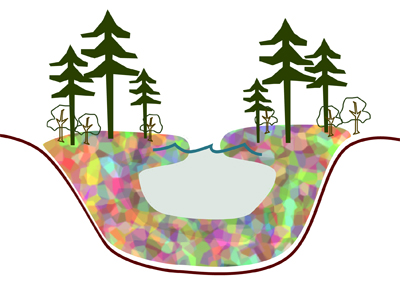

Amphibian populations are in decline in many places around the world, and the reasons become clear during a trip to the Connecticut woods. Amphibians have complex life cycles, during which they may metamorphose from one stage to another multiple times, and rely on a network of diverse and finicky habitats, such as our vernal pools and forests, for their survival. They don't tolerate change well, and thus are early indicators of habitat degradation and pollution.

We went with herpetologist Brian Kleinman to the Enders State Forest in Granby the other day, and discovered a good example in one amphibian's remarkable adaptations. Brian gave us a tour of amphibian habitats here, and shared his knowledge of local inhabitants, such as the Red-spotted newt, along the way.

After years spent wandering the forest floor as a juvenile, the brightly colored red eft, the terrestrial stage of the Red-spotted newt (lower left), grows into a greenish-brown adult stage (upper right), and returns to the water.

Each stage of life is perilous for the Red-spotted newt, and it takes years for them to reach adulthood. They start life as eggs laid in weed choked aquatic habitats in late spring. Weeks later, gilled larvae hatch and feed on insect larvae and small aquatic animals. By mid-summer, many have grown into the red eft stage, and emerge from wetland pools to wander forest floors and colonize new habitats. They remain as efts for 2-7 years until they turn olive green, their tails begin to flatten to aid in swimming, and they return to the water as adult newts. Under some conditions, newts may even skip a life stage.

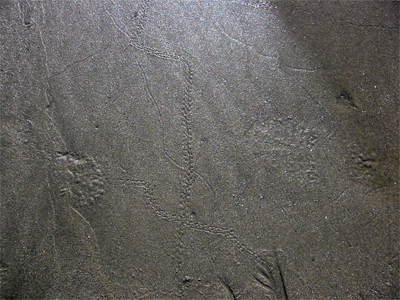

As we walked the trail at Enders, red efts of varying sizes were abundant in the leaf litter, and seemingly everywhere. Their bright orange color serves as a warning to would-be predators foolish enough to consider biting them. Far from appetizing, Red-spotted newts secrete foul tasting toxins through their skin that can cause severe reactions in amphibians and reptile predators.

Of course, this defense is of little use against human impacts such as habitat loss or water pollution. More and more Connecticut communities are taking declining numbers of native amphibians as dire warnings. Towns have begun to work with conservation groups such as Metropolitan Conseration Alliance and Conservation Districts of Connecticut to implement development plans and wildlife managment strategies that are effective at preserving amphibian habitats.

Frogs such as the Spring peeper (left) and Wood Frog (right) are among several other native amphibians commonly found in the Enders State Forest in Granby. Photos by Brian Kleinman. © Perry Heights Press, 2005.