Search for The Magic Bullet (3rd in a series): Measuring Success--And Failure

Global environmentalism entered the digital age when the 2006 Environmental Performance Index (EPI) was released at a meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland last week.

Developed by the Center for Environmental Law & Policy at Yale University and the Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University in collaboration with the World Economic Forum and the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, the EPI pilot study is the first to measure and analyze how some 133 nations around the world currently perform against 16 indicators of environmental protection.

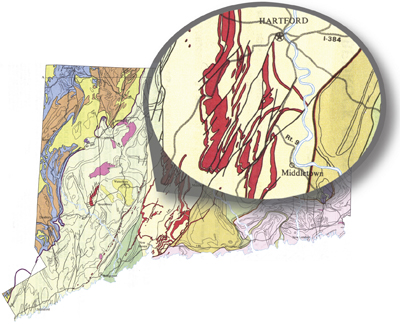

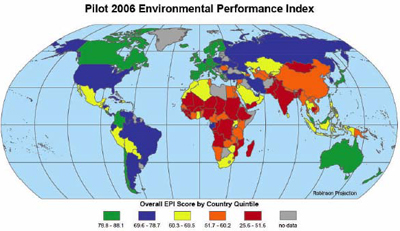

Overall EPI Scores by country (higher scores reflect better overall performance on a scale of 0-100). Green: 78.8-88.1, Blue: 69.6-78.7, Yellow: 60.3- 69.5, Orange: 51.7-60.2, Red: 25.6-51.6, Gray: no data.

“The EPI centers on two broad environmental protection objectives: (1) reducing environmental stresses on human health, and (2) promoting ecosystem vitality and sound natural resource management,” the report says.

“It’s like holding up a mirror and having someone help you see what you couldn’t see before,” Daniel Esty, Director of the Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, told the NY Times. According to the report, “…policymakers in the environmental field have begun to recognize the importance of data and analytically rigorous foundations for decision making.”

The Best & Worst performers

“Top-ranked countries—New Zealand, Sweden, Finland, the Czech Republic, and the United Kingdom—all commit significant resources and effort to environmental protection," the report says. "The five lowest-ranked countries—Ethiopia, Mali, Mauritania, Chad, and Niger—are underdeveloped nations with little capacity to invest in environmental infrastructure or aggressive pollution control and systematic natural resource management.”

The US (78.5) ranks well down, and despite its superpower status, barely manages to crack the top-30. The US performs 28th in the world overall, lagging many European nations, Canada and Malaysia. When viewed among the nations of the Americas, our performance on measures for agricultural, forest and fisheries management is dead last.

The Top 10 (Overall EPI Score) are: New Zealand (88.0), Sweden (87.6), Finland (87.0), Czech Republic (86.0), United Kingdom (85.6), Austria (85.2), Denmark (84.2), Canada (84.0), Malaysia (83.3), Ireland (83.3).

Russia (77.5) ranks 33nd, Brazil (77.0) ranks 34th, China (56.2) ranks 94th, India (47.7) ranks 118th.

Establishing A Baseline

The report’s release serves to put a stake in the ground from which policy and policymakers can be measured in the future. “By identifying specific targets and measuring how close each country comes to them,” it says, “the EPI provides a factual foundation for policy analysis and a context for evaluating performance.”

“Environmental health and ecosystem vitality are gauged using sixteen indicators tracked in six policy categories: Environmental Health, Air Quality, Water Resources, Productive Natural Resources, Biodiversity and Habitat, and Sustainable Energy.”

Work In Progress

As a first effort, the index has its shortcomings, both in terms of methodology and utility. The report acknowledges that there is currently a lack of reliable data, gaps in existing data, and limited country coverage.

These remain as problems to be addressed in future efforts. As it is, the report says the EPI “falls short in covering the full spectrum” of environmental issues such as waste management, acid rain, heavy metal exposures, wetland loss and ecosystem fragmentation.

Methodology and results reporting can also sometimes mask underlying problems. “Among middle-ranked countries, performance is uneven,” the report says. “Russia, for example, has top-tier scores in water but disastrously low sustainable energy results. Likewise, Brazil has very high water scores, but low biodiversity indicators. The US stands near the top in environmental health, but ranks near the bottom in management of productive natural resources.”

“The Pilot 2006 EPI represents a ‘work in progress’ meant to stimulate debate on appropriate metrics and methodologies for tracking environmental performance, enable analysis, and highlight the need for increased investment,” the report says.

A Promising And Powerful Tool

Problems notwithstanding, the release of the EPI represents a great accomplishment and an invaluable tool with far-ranging applicability to addressing modern day environmental issues. Considering the magnitude of these issues, and the threat they present to the quality of life on earth, it serves as a model for a scholarly and systematic approach to bringing about positive change, and as a beacon for international cooperation and collaboration.