Running Before The Blizzard

Yesterday was one of those days when you didn't need a forecaster's warning to know there was a snow coming; you could just feel it. We decided to make the most of the quiet before the storm and were rewarded with the kinds of pleasures that only a day spent hiking up a cold mountain and beachcombing in the face of a building Nor'Easter can bring.

The chill we felt starting up the tower trail at Sleeping Giant State Park in Hamden was gone before we'd turned more than a couple of switchbacks and reached the rock talus. The piles of broken rock here ring the edges of "the giant," a volcanic sill that runs east-west through the park. The sill was formed some 200 million years ago when the supercontinent of Pangaea rifted apart, and magma from the earth's mantle rose and forced its way through the sandstone. Today, the exposed traprock ridge has a profile resembling a giant slumbering on his back.

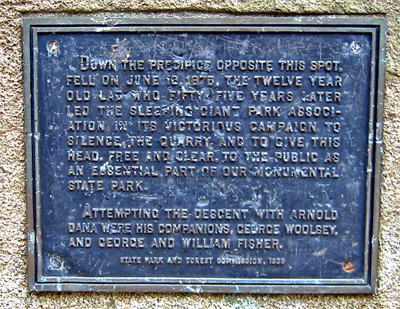

A view along the trail that crosses the Sleeping Giant's neck (above) and a plaque recalling how a spill one boy took here nearly 70 years ago led he and others to work to preserve this place as a park for all to enjoy (below). The quarry they "silenced" is around to the other side, at the top of the giant's head.

Icy patches made the bit of bouldering we chose to do near the top more exciting, and brought us quickly to the castle and its magnificent views of the Hanging Hills further north and New Haven to the south.

Once at the top, there was time to enjoy a lunch of apple slices, pretzels and juice, and to chat with others sitting around the picnic table inside. The sun managed to break through the clouds for a bit, but after a while the cold began to creep back in, and we decided to head back down, and to go on to the beach.

A half hour or so later, we were back in the car, on our way to the Connecticut Audubon Coastal Center at Milford Point to spend some time collecting sea shells.

By the time we got to the beach the Nor'Easter was stirring up whitecaps and blowing stiffly. Somehow, we mangaged to shed the wind and quickly became lost in our search for crab shells, periwinkles, jingles, slippers, arks, razor clams, mussels and oysters. A sand bank piled high with layer upon layer of every different kind of sea shell was irresistible.

We had the entire beach to ourselves, just the way we like it, and got busy picking around the tide flats looking to catch a glimpse of any sparkle of wampum.

Eventually we decided to give in to a cold ache that had soaked into our fingers and retreated inside, to the warmth of the interpretive center. Inside, the marsh here can be seen through the center's big windows and spotting scopes. A couple of Red-Winged Blackbirds hunkered down in a tree that offered little refuge, and seemed to wonder where the spring that appeared to arrive just a few days ago had since disappeared.

Also inside was a wonderful salt-water tank, stocked with various crabs and fish, that held our attention for another hour. By the time we got home the snow was very close and by the time we sat down to eat it began to fall, a perfect end to a perfect day.