Search For The Magic Bullet (8th in a series): Protecting Private Lands

Brooklyn, CT—As a forester and conservationist, Steve Broderick knows better than anyone that it will be private owners who decide the future of much of Connecticut’s remaining undeveloped landscape, especially grasslands, farmlands and forests. He’s also smart enough to know better than to try and tell anyone what they should do with their land.

“The only ‘should’ is that [private landowners] should make informed decisions based on a knowledge of what’s out there on the ground,” Steve says. He’s learned over the course of his career with the UConn Cooperative Extension System about the power of providing people with essential information--and letting them make up their own minds about what to do with it.

You have to be in things for the long haul to be a forester. There’s a place for passion--and talking to Steve you come to know that he is passionate about conserving the rural nature of towns here in the Quiet Corner--but growing trees, and the work of protecting private land from development, requires patience.

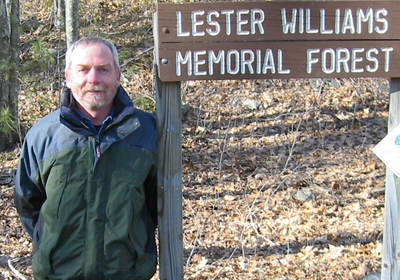

Forester Steve Broderick (above) stands beside a sign commemorating the memorial forest he helped establish through his work with the property’s former owner, the late Lester Williams of Brooklyn.

Outwardly, Steve is controlled, thoughtful, articulate. He has an easy smile and easier laugh--qualities that make him unimposing, trustworthy and quietly effective. He is easy to listen to and many do, from individual landowners to conservation commissioners, to local environmental organizations. So many that since 2001 Steve and his colleagues at the Windham County Extension Center, Ruth Cutler and Holly Drinkuth, have facilitated the protection of 5,156 acres of privately owned land in eastern Connecticut.

The Process Of Protection

Owners can choose to protect lands by selecting from a number of different legal tools. Conservation easements that extinguish rights to subdivide and develop a parcel are among the most common tools used to protect family land. Alternatively, owners may choose to sell or give land to a town, state or an environmental organization and require it be maintained as they wish.

“When you own land you own a bundle of rights,” Steve says, “like a bundle of sticks. You may have one right to hunt, one to fish, one to mine gravel, one to grow and harvest timber, a right to subdivide and another to develop. As a landowner, you can pull one or two of these rights out of your bundle and extinguish them--burn those sticks in a fire. You still own the other rights. Nothing else has changed. A conservation restriction takes out rights to subdivide and develop and extinguishes these rights. All others, including how the land will be managed, remain.”

As a conservation strategy, private and family land protection is one that holds tremendous potential. According to Steve, 85% of Connecticut forestland belongs to individuals and families. Decisions the owners make about whether to conserve or develop their property will go a long way toward determining the character of the state in years to come.

In reality, private land protection is a process that often takes twists and turns and can get thorny. “No two situations are alike,” Steve says. “We’ve had success stories and heartbreakers, where somebody really wanted to do it, but the family couldn’t agree. That’s the way it is.” As much as a landowner may want to see their land protected, their retirement needs or wishes to provide for heirs often make it impossible for them to pass up gains to be had by selling to developers.

“Some people just can’t afford to,” says Steve. “I worked with a fellow who has been a hard working man his whole life. His job had no pension plan. He’s sitting on a beautiful hundred-acre farm--and this is his 401K. You can’t expect somebody like that to give land away, give development rights away. We have funding programs, but there is never enough to go around.”

Clearing The Path

“Half of landowners intend to protect some or all of their land from development,” Steve says, referring to results of a survey he conducted, ”but experience shows only a tiny fraction of landowners do it. Why? Lots of reasons. Some of it is money and family, some don’t get around to doing it, but the big reason is that protecting land is very complex. It’s not straightforward. It’s intimidating. Owners don’t know where to turn or how to decipher information.”

As a result, opportunities to protect a parcel come and go quickly. It’s essential to connect with landowners when they decide to sell and want to understand their options. “It one of those ‘teachable moments,’” Steve says. “People have to be ready. When they are they have to know where we are and how to get hold of us.

“That’s what got us involved with education. We offer a workshop called ‘Protecting Family Lands.’ It’s designed for people in this mode of ‘I’d like to know my land will be protected, but I don’t have a clue what to do.’ We also have a publication with questions owners can ask themselves to begin a protection plan and things they need to think about.

“We talk about tools for protecting land, bundles of rights, what a conservation easement is, and end with tax breaks and funding programs for people who want to protect their land.” Recently, they added a course for real estate brokers. “Other than owners, the development community has the most impact on the landscape. We can’t ignore them.

“We teach realtors to use natural resource maps to get a feel for environmental concerns. We teach about protection and development options from finding a conservation buyer, to writing conservation restrictions, on down to so-called cluster subdivisions that protect what my friend [conservation attorney] Fritz Gahagen calls the ‘integrity if not the entirety.’”

Listening To What Owners Want

Steve’s goal is to help people make their own, informed decisions. He offers assistance in navigating the process, but owners set the terms. “We ask owners ‘who do you want to see own the land when it’s protected?” Steve says. “Do you want to own it with reserved life use? Do you have heirs that you want to own the land? Would you rather a conservation organization own the land or would you rather your town or the state own it?”

In establishing the Lester Williams Memorial Forest, great care was paid to honoring the owner’s legacy, and his stewardship ethic. Together with The Wolf Den Land Trust, a subsidiary of a non-profit association, The Eastern Connecticut Forest Landowners Association, a plan was developed based on the owner’s legacy.

“Lester was a farmer, the First Selectman of Brooklyn at one point, and President of the Brooklyn Fair,” Steve says. “He cut wood on the property and sold pulp to the local mill. He was also an outdoorsman and ardent bird watcher. The Land Trust developed a profile of how Lester Williams managed his land and why. What motivated him? Then, a forester was hired to develop a stewardship plan built around Lester’s interests so that the property will be managed the way Lester would have wanted it managed.

“Every landowner is different, so every stewardship plan [written by the Wolf Den Land Trust] is based on a combination of two things: the particular forest and ecosystems on the ground, and the goals and interests of the owner. These are matched to create a good plan.”

Leading Change At The Community Level

It’s easy to see that helping protect land like Lester Williams’ is work that Steve finds personally rewarding. When asked he’ll recall other examples he cherishes. There’s the parcel in Thompson that preserves a bog and its unique Black Spruce tree and pitcher plant community, a case he worked on with Dick Booth of the Windham Land Trust.

There is the 140-acre former Boy Scout camp that straddles the line between Eastford and Woodstock that is now a park the two towns steward together. “It’s a beautiful property,” Steve says, “which is, in fact, a key part of a much larger block of protected open space. It’s just a stone’s throw from Yale Forest to the north, and the Natchaug State Forest to the south.

“It was a very nice success. The two towns and the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection each came up with a third of the purchase price. The Nature Conservancy paid the closing costs and survey costs. It was a true partnership.”

Rather than dwell on individual successes, however, Steve keeps the bigger picture in view. “The scarcer land gets the more concerned people are,” Steve says, “but it’s hard to get people to perceive landscape fragmentation, a more nebulous issue, as the problem. The challenge is to mobilize them to protect land resources.”

In addition to working with landowners, he also works to inform communities about setting conservation priorities. Just as his experience can inform owners about their land protection options, he sees a need to inform communities about protecting parcels of larger, regional importance. Fit together like pieces of a puzzle, local decisions can protect wildlife or biotic corridors also imperiled by the pace of development in Connecticut today.

“We also work with land use commissioners at the municipal level. In Connecticut, responsibility for planning and regulating growth is delegated to towns,” Steve says. He works with the Green Valley Institute to provide information towns in eastern Connecticut along the Quinebaug-Shetucket National Heritage Corridor can use to make land use decisions.

“We’re working to make sure that people have good information on which to base their land use and environmental decisions, whether you’re talking about an individual landowner, a town, a land use board or commission, or whomever it may be.”

It seems there isn’t a part of land protection that Steve isn’t thinking about or involved with. “My role is that of a front man who gets things rolling,” says Steve. “I sweep the media. I bring in landowners who have interest, give direction and education. I connect them with conservation commissions or land trusts. Those folks get the deal done while I go on to the next case.”