Geology, Hurricanes and the Floods of '55

This year's catastrophic hurricane season brings back memories of 1955 for many who survived the floods that hit Connecticut during late summer a half century ago. On August 12 & 13, Hurricane Connie brought 8 inches of rain. On the 18th, Hurricane Diane brought more. The Hartford Courant reported “normally docile brooks were transformed into menacing monsters by relentless rain." The ground saturated by Connie, Diane caught people by surprise.

In a little over 24 hours, more than a foot of rain fell in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Rivers, streams, lakes and ponds spilled over, sending torrents of water through towns. A state record 14.25 inches fell in Torrington; Westfield, MA had nearly 20 inches. By the afternoon of Aug. 19, the storm passed. 87 people died, communities were wrecked, and losses were hundreds of millions of dollars.

The geology and hydrology of Connecticut show how the storms led to a catastrophe. The landscape has a decidedly north-south grain that goes back to continental collisions in the deep past. Since then, it's been water, flowing south toward the Atlantic, that has shaped local hills and valleys.

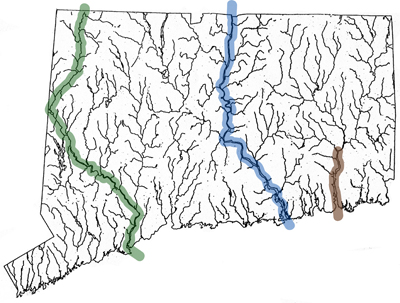

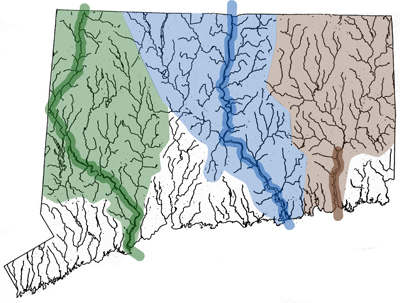

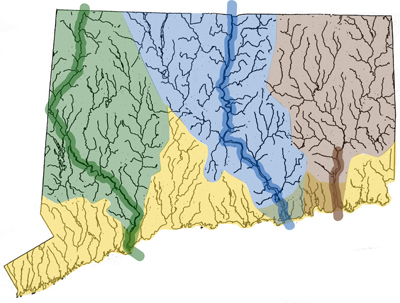

Today, the state's three major rivers, the Housatonic, Connecticut and Thames, are the primary watercourses that carry runoff to the Long Island Sound. They are fed by a great many smaller streams and rivers that drain upland areas across the northern two-thirds of the state.

Water gathers into bigger and bigger watercourses as it rolls downhill. In Connecticut, water streams down along erosional planes that slope to the Atlantic, as it has done for perhaps millions of years. Along the way, it gains speed, volume, and power. The volume of water that fell in August 1955 quickly exceeded the rivers' natural capacities, and the power of the runoff grew to be tremendous.

Nearer the shore, areas surrounding many shorter rivers were also affected. Along the southern third of the state, these shorter rivers drain an area referred to as the coastal plain. In many cases, these are also fed by adjoining streams and smaller rivers, and the effects of the flash floods on these watercourses were similar.

In most years, the state's streams and rivers work as an efficient natural drainage system, carved out over large spans of geological time. There are times, however, when the nature of Connecticut's watercourses leaves the possibility that they can be overwhelmed by extreme weather such as hurricanes and flash floods.

Controls such as the many dams that have been built since 1955 have been designed to provide greater protection and limit damage. According to the Army Corps of Engineers, these dams can be used to better control water flows. Forecasting and our knowledge of how hurricanes behave has also improved.

Yet, these improvements have still to be tested by a series of storms, back to back, as occurred fifty years ago. The geology and hydrology of Connecticut remains largely as it was, and damaging hurricanes can be expected to hit the state at least every hundred years or so. While many see a repeat of anything like what occurred in 1955 as unlikely, only one thing is for sure. There's no way to know what Mother Nature may have up her sleeve next.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home